This year has been tough, there’s no doubt about it. Everybody has undoubtably suffered in one way or another, that’s a given. But parents of children with complex medical or special educational needs have been starved of support in ways that this time last year, were almost unthinkable.

In all honesty, I could probably write a lengthy novel on caregiver burnout and the long-term impact of not caring for yourself whilst you’re caring for somebody else. It’s not selfish, it isn’t a luxury. Looking after yourself when somebody, especially a child, is relying heavily on you to have their basic needs met is a necessity.

I was so determined at the beginning of this pandemic to protect my child with every ounce of me that I convinced myself whilst telling others that it didn’t matter what impact it would have on my long-term health or mental wellbeing. I really didn’t care about me as we were thrown into the world of fear and unknowns. As long as my child was safe and protected from what seemed to be, a very frightening outside world then nothing else mattered. Everything else would be fine.

In protecting my child, in starving myself of all offers of support altogether, in isolating us into such a tight bubble that meant it were just me and him for months on end, I was in fact causing myself significant and debilitating distress. The consequences were that I snowballed my way right down to rock bottom. I couldn’t see what I was doing. I couldn’t see that I was on the edge of a complete burnout. I couldn’t see that I needed support. Many people around me could but I refused to see what was glaringly obvious, for all that mattered was my child.

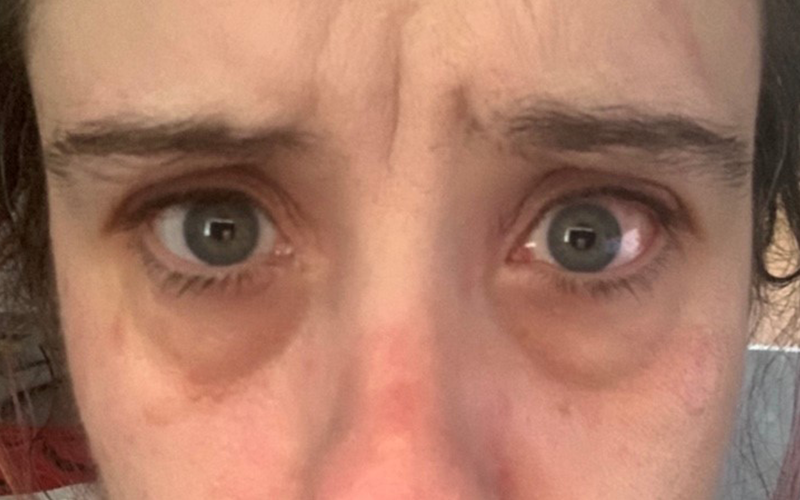

“I’m fine”. Ah those two little words that can hide a multitude of sorrow and sadness. They became my lockdown motto. That and “I’m just tired”. I was tired. I was exhausted. But it was a kind of tiredness that sleep alone was never going to fix. I needed more than sleep. I needed time. I needed to step away from the bubble of being a carer to find myself again. In that moment I just couldn’t see it.

I was blind to the dangerous and dark situation I’d inevitably landed myself in.

I’d forgotten what it felt like to just be Jaxon’s Mummy. I was his carer, his therapist, his nurse. I wore all the different hats that his medical team wear whenever he’s in their presence. I’d forgotten how to just be Jaxon’s Mummy. I feel sad as I type that. How do you forget how to be your child’s parent? Don’t get me wrong I was doing the necessities to keep him fed, clean and looked after. Medically he never suffered, those needs were always met but I fear that during the time I’d become so consumed in protecting him, he lost his Mummy for a short while.

This is the reality of carer burnout. I genuinely believed it didn’t matter what happened to me as long as my child was protected but I couldn’t have been more wrong. By the time I realised how bad things had become I was in a full state of physical, emotional and mental exhaustion. I struggled daily with overwhelming sadness, I couldn’t sleep and then it took every scrap of energy I had to get myself out of bed in the morning. I struggled to find any joy in my life.

It felt like I was carrying the weight of a thousand universes on my shoulders as I struggled to keep myself afloat, not knowing if there would be an end in sight anytime soon. I was becoming angry. I was forgetful, my life had become a series of calendar reminders and post-it notes. The anxiety that I’d managed to battle and all but overcome many years ago, was back with a vengeance.

Not to mention I’d lost all sense of my own identity. I was feeling resentful of everybody around me. I was eating less. I found no entertainment in anything that I used to. I let all my programmes record and build up, instead sitting in silence, tearful every evening. I didn’t know who I was anymore. I’d lost all sense of self. My thoughts were irrational, and the traits of my personality disorder were seeping into my day to day life. I felt like I couldn’t talk to anybody, we’re all struggling after all. I didn’t want to be a burden so I battled through. It’s always been my way.

Asking for help has never been a strong point of mine.

Luckily on one of Jaxon’s many hospital admissions, I was taken to one side by a member of his team who has been on this journey with us since the beginning. I could see she knew how bad things were although I slapped on my “I’m fine” smile and put up a pretence that actually I really was alright. I wasn’t though. I was crumbling. She all but begged me to allow somebody, a nurse who I know well, to come into our home for a few hours each week to give me some support. It felt that it wasn’t really a request, more an order. But the reality is, I’m so stubborn and determined when I put my mind to something, I just can’t detract from it. I needed to be told.

And so my journey started to find my way out of this place, that pit at rock bottom. In the last few weeks, I’ve been able to accept more help from Jaxon’s Dad and my parents. I’ve opened my eyes to how bad things were. I’ve realised how serious things were becoming and how much I needed to change. It’s enabled me to find the courage to venture out into the big wide world once again and mix with people safely. It’s been just what I needed. It’s given me that sense of being more than just Jaxon’s Mum which ironically makes me so much more of a better Mum to him.

It’s not a weakness to ask for help. It’s a strength. It takes real bravery to ask for or accept help when it’s offered. It’s something I will continue to work on. If you’re feeling burnt out like I did then take my word for it when I say it will not get better on its own. Only you can change it, but you can’t do it alone.